If a Producer Sells a Song, Do They Still Get Royalties? Master Rights vs Publishing (Brutus vs Richie Explained)

- Haitianbeatz

- 4 days ago

- 8 min read

By Haitianbeatz

If you’ve ever heard someone say, “I bought the song, so I own everything,” you’ve heard the most common myth in music rights.

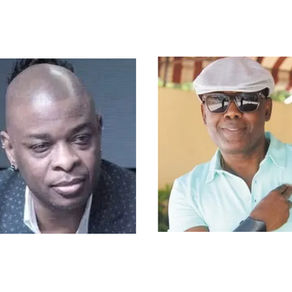

The Maestro Brutus vs Richie dispute around Zenglen (as described in interviews) is a perfect case study because it shows how fast people mix up two different things: owning the master recording and owning the songwriting (publishing). Those aren’t the same. Buying one doesn’t automatically buy the other.

Richie’s side, as described, is that he never sold his royalties or credit rights, and that he previously appeared in credits as composer, lyricist, and arranger. Brutus’s side, as described, is that he paid for the songs, owns the masters, and therefore owns royalties, with later compilations listing Brutus instead of Richie.

This article explains what usually happens when a producer sells a song (or is paid for a song), which royalties can still come in, and which documents decide who’s right. This is general education, not legal advice.

Song ownership is usually split into two buckets: the master and the songwriting

When people argue about royalties, they often argue about “the song” like it’s one single thing. In reality, music rights usually split into two separate copyrights.

Think of it like a house and a floor plan. The master recording is the actual finished audio you can play on Spotify. The composition is the underlying blueprint: melody and lyrics (and sometimes protected parts of the arrangement, depending on the situation).

A single payment can cover either bucket, or both, but only if the deal says so. That’s why two people can both be telling “their truth” in interviews and still be talking about different rights.

Also, results depend on contracts and local law. Haiti, France-related systems (like SACEM connections), and the United States can treat details differently. Still, the core idea stays steady: master ownership does not automatically equal songwriting ownership.

The master recording (sound recording): who owns the released audio

The master (also called the sound recording) is the specific recorded performance fixed in audio form. It’s the exact track listeners stream. Whoever owns the master can usually control how that recording is used.

Master ownership often sits with:

A record label

The featured artist

An investor or production company that financed the recording

A producer, but only if the agreement puts the master in the producer’s name

Owning the master generally includes the right to:

Distribute the recording (sell it, stream it)

License the recording (for films, ads, compilations, games)

Collect master-side income from platforms and licensees

Here’s the key point for the Brutus vs Richie type of dispute: master ownership mainly controls recording income. It does not automatically give someone the right to claim they wrote the melody or lyrics. It also doesn’t automatically transfer the writer’s royalties paid through songwriter and publisher channels.

So, if Brutus truly owns the masters to past Zenglen recordings, that could give him strong control over the audio releases and master income. But that fact alone doesn’t settle composer and lyricist credits.

The composition (publishing): melody and lyrics, plus writer credit

The composition is the underlying song: the melody, the lyrics, and the core musical expression. This is what you’d play on a guitar and sing in a room, even if you never recorded it.

Composition ownership often belongs to:

The songwriter(s)

A music publisher (if the songwriter signs or assigns rights)

A buyer (only if there’s a written assignment of publishing)

Composition rights typically include the right to:

Collect performance royalties (radio, live venues, TV, many streaming uses)

Collect mechanical royalties (copies and interactive streams)

Approve and collect sync fees (use of the composition in film/TV/ads)

Writer credit matters because collection systems run on data. If Richie was credited for years as composer, lyricist, and arranger, that credit history lines up with the idea that he owned (or at least claimed) composition rights. If later releases removed his name and replaced it with someone else’s, that can cause real payment changes through publishers, PROs, and metadata pipelines.

When a producer sells a song, which royalties can still keep coming in

When a producer “sells a song,” that phrase can mean very different deals. Sometimes it’s a one-time fee for production services. Sometimes it’s a buyout of the producer’s backend on the master. Sometimes it’s a sale of the master. Sometimes it’s a publishing assignment. Sometimes it’s all of the above in one contract.

The simple rule is this: royalties follow rights. Royalties only transfer if the rights transfer, and the transfer normally needs to be in writing.

So, yes, a producer can still receive royalties after a sale, but only for the rights they kept. And no, paying someone once does not automatically erase their royalties unless the paperwork says it does.

Master-side money: artist royalties, producer points, and neighboring rights

On the master side, producers often earn money in a few ways:

Producer fee (upfront): A flat payment for producing. This alone does not mean the producer sold anything beyond their labor, unless the contract says it includes a buyout.

Producer points (backend): A percentage of master revenue (often called points). These payments usually come after recoupment, meaning the label or owner recovers costs first.

Master ownership: Sometimes the producer owns the master and licenses it. Other times, the producer assigns master ownership to a label or investor.

If a producer sells or assigns the master, they may still receive producer points, but only if the deal keeps points alive after the transfer. In many buyouts, the producer trades points for a larger upfront payment, and the contract says the producer won’t receive future master royalties.

Neighboring rights can add another layer. In many countries, performers and master owners can receive neighboring rights income when recordings are broadcast or played publicly. That income may be separate from songwriting royalties. A producer who is also a performer might have neighboring rights even if they don’t own publishing.

The investor question raised in the interviews is a practical one: if investors paid Richie for his work, what did they get? Payment could mean:

They funded recording costs and received master ownership (or a share).

They paid a producer fee only, with no ownership.

They advanced money that recoups from master income.

They bought a catalog interest.

If investors truly bought the master, it would be normal for the master ownership to sit with them (or their company), not automatically with the person compiling albums later, unless rights were assigned again. That chain of transfers matters.

Songwriting money: performance, mechanical, and sync royalties

Songwriting royalties usually keep flowing to the writers and publishers unless those composition rights were assigned away.

Performance royalties come from public performance of the composition, like radio, TV, live venues, and many uses tied to streaming. These are tracked and paid through PROs (performing rights organizations) or similar societies.

Mechanical royalties come from reproductions of the composition, including downloads, physical copies, and interactive streams (where the listener chooses the track). Who collects depends on country and distribution method.

Sync is money paid when the composition is paired with visuals (film, TV, ads, and many online uses). In the HMI, noone pays for those things. Sync deals often require permission from the composition owner, even when someone else owns the master.

This is where Richie’s claim about registrations matters. If he registered works with SACEM, then later, when he tried to move catalog administration toward ASCAP, he says he was notified that the songs were already registered under Brutus’s name and another entity. That kind of conflict often points to a data and chain-of-title problem: someone filed registrations that don’t match the earlier splits, or the splits changed on paper and not everyone agrees they changed.

Also, Brutus reportedly acknowledged in an interview with James Pierre that Richie was the sole producer of the album, describing how the album sounded strong enough to invest in after Richie played it. That statement supports Richie’s role as producer, but it still doesn’t answer the publishing question. Producing a record and owning the composition are related sometimes, but they’re not the same thing.

Applying the rules to the Brutus vs Richie claims: what each side would need to prove

Based on the facts described, the dispute seems to center on two claims that can both sound reasonable until you separate them.

Brutus claims he paid for songs and owns the masters, and that owning the master gives him rights to the songs.

Richie claims he never sold his royalties and credit rights, and that he was credited for years as composer, lyricist, and arranger, then removed on later compilations.

In most music business setups, these claims touch different legal lanes. The winner is usually the party with the cleanest paperwork and the clearest chain of title for each right.

Does owning the master mean you can replace the songwriter credits

Typically, no. Owning the master does not normally give someone the right to claim composer or lyricist credit. Those credits tie to the composition. To replace a songwriter’s credit legally, there usually needs to be a valid written transfer of composition rights, or a clear agreement that the work was created under a structure where the buyer is treated as the author under local law (rules vary, and not every country treats “work made for hire” the same way).

Arranger credit is a little tricky. Some arrangements can be protected if they add original musical expression, but an arrangement credit usually does not erase the underlying composer and lyricist. A new arrangement can sit on top of an existing composition, like a new paint job on the same house.

When credits are removed or swapped on a compilation release, it can create practical problems fast:

PRO payments can reroute.

Publisher claims can change.

Distributor metadata can overwrite older data on platforms.

YouTube and social platforms may match the wrong ownership records.

So even if Brutus has master rights to compile and release recordings, replacing Richie’s writer credits would usually require separate composition authority.

The paperwork checklist that usually decides who is right

When a dispute hits this stage, opinions stop mattering and documents start mattering. A good approach is to “follow the chain of title,” meaning you track who owned what at creation, then every transfer after that.

Here are the key items that usually answer a producer-sold-song royalties question:

Producer agreement: Does it say Richie was paid a fee only, or did he assign master rights, points, or both?

Catalog or asset sale agreement: If Brutus “bought the songs,” what exactly was sold (masters, publishing, both), and was it in writing?

Split sheets: Any written songwriting splits for each track, signed by the writers.

Publishing assignment: A document where a writer transfers part or all of composition rights to someone else.

Label or distribution contracts: Who delivered the masters, and who was listed as rights owner for the sound recordings?

Copyright registrations (where applicable): What was registered, by whom, and when?

PRO or society work registrations (SACEM, ASCAP, and others): Who is listed as writer and publisher, and were there later amendments?

Compilation licensing paperwork: What permissions were granted to re-release old albums, and did those permissions include credit changes?

For Brutus to be right on publishing, the paperwork would usually need to show that Richie assigned composition rights (writer share and or publisher share) or agreed to be uncredited. For Richie to be right, he’d want documents showing he kept his writer and publisher interests, plus a consistent history of registrations and credits that match his claim.

If the core problem is incorrect registrations (for example, works appearing under Brutus’s name at SACEM or in the pipeline toward ASCAP), correction often involves formal disputes through the society, backed by contracts, split sheets, and evidence of authorship.

When a producer sells a song, royalties don’t vanish by magic, they move only when rights move. The master recording and the composition are two separate buckets, and confusing them is how disputes like Brutus vs Richie start. Owning the master can control releases and master income, but it usually doesn’t let someone rewrite composer and lyricist credits. Credits also affect payments, since PROs and publishers follow the data they’re given. If you make music, protect yourself early with split sheets, clear contracts, and correct registrations, before compilations and re-releases happen. In this specific dispute, only the signed agreements and the registration trail can answer who’s right.