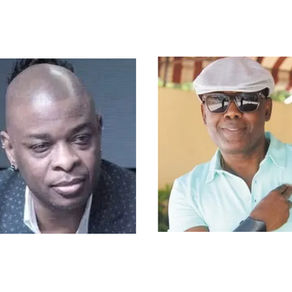

Ralph Cadet of Chic Club and the 1980s HMI Party Blueprint in New York

- Haitianbeatz

- Jan 12

- 7 min read

By Moses St Louis

If you want to understand how the Haitian Music Industry (HMI) grew in New York, you don’t start with streaming numbers. You start with the people who booked the rooms, took the risk, and built trust one party at a time.

That’s why conversations with pioneer HMI promoters matter. In a recent talk with Ralph Cadet of Chic Club, he shared how events really worked in the 1980s: who got booked, where the crowd went, how promotion happened before social media, and what the money looked like.

This article is simple on purpose. It’s names, venues, dates, and real numbers, the kind of details that help protect HMI history and still teach today’s promoters a few lessons.

How did Chic Club come about

Chic Club started the way many real ideas start, with friends hanging out and noticing a need.

Ralph said the founders used to hang out together, and during one of those hangouts at Jean Rigaud’s house, they came up with the concept. They saw the need for something consistent for the Haitian community, a place to unwind after a long work week.

Ralph also came up with the name “Chic Club.” He said it came from the music group Chic, which he listened to while he was in the Army, including a popular song he remembered with a “Chic, freak out” hook.

Back then, promoting could be very lucrative when everything hit right. Ralph told me he bought his first house after a long Thanksgiving weekend where they organized a few parties, starting on Wednesday night, the day before Thanksgiving. His share of the profit was enough to put down a deposit on a house.

That’s the part people forget. These weren’t just parties. For some, they were a path to real stability.

Who is Ralph Cadet of Chic Club, and why his story matters to HMI history

A promoter’s job sounds easy until you’ve done it. You find a venue, secure talent, advertise, manage problems at the door, and hope the crowd shows up. If the night goes bad, the promoter owns that loss. If it goes great, the promoter earns a name people remember.

Ralph Cadet is one of those early names in the Haitian party circuit. His work with Chic Club helped shape a time when Haitian parties weren’t just nights out, they were meeting points for the diaspora and fuel for Haitian music in New York.

This isn’t rumor or recycled talk. These details come from Ralph’s own memories, shared directly.

Chic Club was built with other co-founders who were active in the scene: Lesly Murad, Ricot Duverglass, Jean Rigaud Fidei. Ralph is still around today, still promoting, just not at the pace of earlier years. He recently organized the Tabou Combo tribute to Shoubou and is also part of Tabou’s management team.

What the HMI party circuit looked like in early 1980s New York

In the early 1980s, the HMI party circuit ran on a few basics: DJs who could hold a room, promoters who could fill it, and venues willing to host a Haitian crowd week after week.

Queens shows up in this story for a reason. Long Island and Brooklyn. People traveled for good parties, especially when the flyer promised the right DJ, the right band, and a safe room with a serious vibe.

Word of mouth did a lot of the work. But it wasn’t random. Promoters worked their networks hard, and every event was a chance to build the next one.

The difference between a DJ event and a live band party back then

A DJ event could be lighter to run. You still needed a room, security, and promotion, but the setup was simpler.

Adding a live band changed everything: higher fees, more gear, more timing issues, and more risk. A band night could raise your status fast, but it could also drain your budget if attendance fell short.

That contrast shows up clearly in Ralph’s numbers later on.

Ralph told me his first event was Valentine’s Day 1981, booked at the Raceway Hotel in Queens, featuring DJ Action Jackson.

That date choice wasn’t luck. Valentine’s Day is already emotional, social, and built for a night out. Pair that with a DJ people respected, and you’ve got a clean formula: give the community a reason to dress up and a reason to trust the music.

What made a DJ a headliner in 1981

In 1981, a DJ wasn’t background music. The DJ was the engine.

A real headliner DJ could do a few key things all night:

Read the room fast and adjust without stopping momentum

Blend Haitian favorites with what the crowd was asking for

Keep energy steady so the dance floor never died

Booking DJ Action Jackson for that first event sent a signal: this wasn’t a thrown-together party. It was planned by someone who respected the crowd.

Direct mail promotion, building a mailing list at every event (before social media)

Ralph’s main promotion method was direct mail. No apps, no event pages, no mass texting. He built a mailing list by hand, event after event, then used it to keep rooms full.

The idea is almost old-school marketing poetry. You host a great night, then you stay in touch with the people who proved they’ll come out.

Consistency was the trick. He didn’t collect names once. He collected names every single event.

How the mailing list was built, sign-up sheets, friends of friends, and community spots

The list came from simple sources that worked because they were personal:

Sign-up sheets at events (often near the door or a visible table)

People bringing friends and sharing contacts

Community connections that spread through Haitian social circles

Accuracy mattered. Misspell a name, write a wrong address, and that contact is gone. Over time, a clean list became a real business asset. It wasn’t just “promotion.” It was ownership of your audience.

What direct mail pieces likely included, dates, venue, music, and a clear call to show up

Direct mail worked best when it stayed clear and direct. The message needed to answer basic questions fast:

What’s the event, when is it, where is it, who’s playing, what does it cost?

No long speeches. No mystery. A strong date, a trusted venue, and recognizable talent did most of the talking.

The economics of 1980s HMI parties, what it cost, what tickets cost, and how profits were made

Behind every classic party story, there’s a spreadsheet in someone’s head. Ralph shared numbers that show how promoters thought about cost, demand, and risk in real time.

These figures are based on Ralph’s recollection, and they reflect how the market worked in that era.

Top Vice in 1987, paying the band $700, charging $20 per person

Ralph said his first party with a band was Top Vice in 1987. He paid the band $700, and charged $20 per person.

That one detail tells you a lot. Just to cover the band fee, you’d need to sell:

$700 divided by $20 = 35 tickets

And that’s only the band. It doesn’t include the venue, sound, printing, security, or any other costs that come with a real night. So the real break-even number would be higher.

Still, the pricing shows confidence. A $20 ticket in that era says the crowd saw live Haitian music as something worth paying for.

Skandal’s only New York performance for him at Plattduetsche, and a $250 venue rental

Ralph also shared a standout booking: the only time Skandal performed in New York was for him (as he remembers it), at Plattduetsche in Long Island.

At the time, he paid $250 to rent the venue.

A lower rental cost can help, but it doesn’t make the job easy. Long Island logistics can add pressure: travel, timing, and crowd expectations all go up when you’re asking people to leave their usual neighborhoods.

Bookings like that also build reputation. When you’re known for bringing rare moments to the community, people take your flyers seriously.

Radio, hype, and star power, when Eddy Publicité was the only station and Sweet Micky was a draw

Ralph pointed out that Eddy Publicité was the only radio station back then. When media choices are that limited, the main station isn’t just a channel, it’s the center of gravity.

He also said he used to hire Sweet Micky, a name that could pull attention fast. Star power mattered even more when you couldn’t rely on dozens of outlets to spread the word.

How one radio station could make or break an event

With one major radio source, promotion got focused. You didn’t try to be everywhere. You tried to be in the right place at the right time, with a message people could repeat.

It also meant relationships mattered. If the station respected your events, the community heard about them. If not, you had to work twice as hard through street promotion and direct mail.

Why hiring big personalities helped promoters stand out

Big personalities create confidence. Fans think, “If that artist is on it, the party will be good.” That trust moves tickets, and it pushes people to bring friends.

For Chic Club, those bookings weren’t just entertainment. They helped build a brand people could name, describe, and remember.

Ralph Cadet’s Chic Club story makes the 1980s HMI party era feel real because it’s built on details: a first event on Valentine’s Day 1981, a Queens hotel room, direct mail lists, and clear costs like $700 for Top Vice and $250 for Plattduetsche.

The lessons aren’t complicated. Start with reliable talent, collect contacts at every event, know your numbers, and use the media channels that exist in your time. Most of all, keep the story alive, because memory is history when the flyers fade.

If you were around that era, what do you remember most, the venues, the DJs, or the nights the whole community seemed to show up?

Comments